The Translucency of Color

The three known basic properties of color are:

The three known basic properties of color are:The hue: red, yellow, blue, green etc.

The brightness: light, dark (and the graduation between)

The colorfulness: intensive, vivid, muted, pale, and similar

As a result of his systematic examination of the traditional multilayer technique and his work with glazes (more or less transparent layers), Egon von Vietinghoff inevitably discovered another property of color: translucency.

Gauguin's and van Gogh's colors and those of the impressionists frequently are very intense. Since these artists usually applied opaque paint, it lack the transparency of glazes, and therefore nuanced transitions are eliminated. (see "Cloisonnism" and "Expressionism").

The picture parts lie next to each other rather equally in intensity of color and the representations therefore seem more flat, now and then even strikingly so. In the traditional painting the picture's depth is developed not only from the prospective but by means of the applied paints in various more or less translucent layers.

In the past, its effect had definitely been shared by masters with pupils in the natural course of study. During the Rococo period, the interest in translucency had temporarily decreased, especially in the dark glazes, but was revived once more, till it came to a standstill with Impressionism.

When Vietinghoff started to paint, no sound explanation of the translucency phenomenon or any detailed instructions on how to handle it existed. In the academies he visited, it was no longer taught and the sparse records on paint mixing did not replace the loss of the oral and practical tradition of multilayer oil-resin and glaze painting with its translucency effect.

Vietinghoff's awakening, his education and his beginnings as a painter belong to the period of Modernism and Expressionism, as well as to the revolutions of Dadaism, Cubism, Bauhaus, Abstraction and Surrealism. When he moved to Paris to begin his career, the average age of a selected twenty European painters, thought to be the most influential of time including Chagall, Matisse, Delaunay, Picasso, Malevich, Kandinsky, Klee, Feininger, Arp, Mondrian, was 43 years. Thus, they had reached the age where they had surpassed their initial phase of searching and experimenting and had firmly established themselves to dominate the artistic scene.

All these rising trends did not correspond to his ideas – his philosophy would originate from another point.

Thus, he became a self-educated person and

acquired the necessary skills through his own studies and comparisons of the original paintings in the museums with the results of his experiments in his studio.

In parallel to the lifelong evolution of his work, he recorded all his observations and experiences, over decades, which resulted in the Manual of the Painting Technique. Here, he also defined the translucency of color, in what is believed to be the first ever description of this kind. He stated that translucency is the fourth property of color, which indicates the saturation of light in color.

Translucent: light-transmissive, light saturated (opposite: reflecting light, opaque)

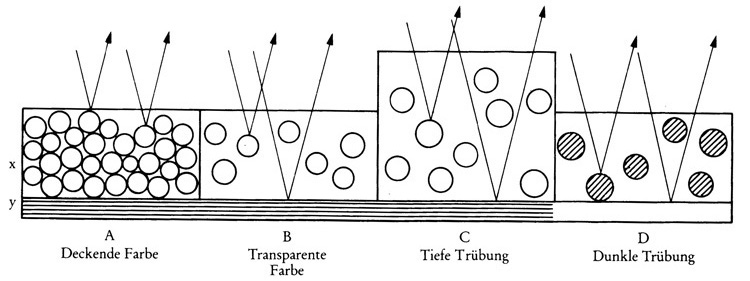

Any paint can be translucent or opaque (covering the base completely), white as well as black. The degree of how much color is translucent or opaque depends not only on the quantity of color but also on the density of pigments and binders, as a result of the treatment of the pigments and other ingredients. Pale colors can be less translucent than bright ones if they reflect more light and do not allow underlying color to shine through the upper. Conversely, dark paints can be made and applied in such a way that they seem more translucent than bright colors.

Any paint can be translucent or opaque (covering the base completely), white as well as black. The degree of how much color is translucent or opaque depends not only on the quantity of color but also on the density of pigments and binders, as a result of the treatment of the pigments and other ingredients. Pale colors can be less translucent than bright ones if they reflect more light and do not allow underlying color to shine through the upper. Conversely, dark paints can be made and applied in such a way that they seem more translucent than bright colors.  This is the subject of Vietinghoff's

This is the subject of Vietinghoff'sspecific interest to better understand the difference between the so called additive and the subtractive paint mixing.

Additive refers to the mixing of paints to obtain a final paint before its application on the canvas; subtractive mixing means the final color on the canvas as a result of several translucent layers. The knowledge of translucency is crucial for the multilayer oil-resin painting; it is its characteristic artistic method. If translucency is not the aim, it would not make sense to use the multilayer technique.

The combination and interaction of all layers, exclusively on the canvas, result in a new color quality, which is unattainable by a paint mixed solely on the palette.

The color finally produced in the beholder's eye has a translucent quality. Thus, the overall impression of painting in the multilayer technique (for instance, in the work of Vermeer, Goya or C.D. Friedrich) is so fundamentally different than that of paintings "alla prima", in the one-layer or wet-on-wet technique (see Monet, van Gogh or Kokoschka).

This obvious difference in the visual result is independent of any individual expression or stylistic trend of the respective period in art.

The difference between a translucent and a non-translucent painting is comparable with the difference between an image on a slide and its paper copy, through which light is unable to shine.

The difference between a translucent and a non-translucent painting is comparable with the difference between an image on a slide and its paper copy, through which light is unable to shine. The final color, which is a result of various layers, is translucent because the light is not reflected on the first surface but penetrates the layers of paint and is reflected several times on different levels.

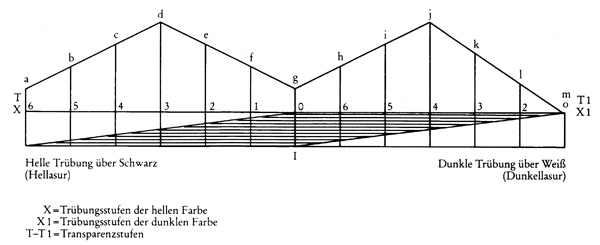

According to Vietinghoff, each glaze alone is not translucent but more or less transparent with the resulting sum of all layers being a translucent color.

Analyzing his definition, we recognize the problem that in German the term "translucency" is not common but replaced by "transparency" – a problem which in other languages such as English, French, Italian or Spanish does not exist.

What Vietinghoff means by "transparency" is synonymous with "translucency", the degree of saturation of light in the final color reaching the beholder’s eye, as a result of the multilayer painting.

By using this technique there are several more or less transparent and rather liquid layers called glazes.

Due to the varying degrees of light permeability of each layer, the light reflects gradually on various levels.

The "deep light" is the light which penetrates all layers and reflects from the neutral base (white, cream or grayish) which usually is perceived only unconsciously. On the way back, the same light is reflected by the bottom side of the layers which it has already penetrated.

The refractions create multiple unnoticeable interactions, some from layer to layer according to their properties and some others within a single layer as a phenomenon of multi-beam interference.

The refractions create multiple unnoticeable interactions, some from layer to layer according to their properties and some others within a single layer as a phenomenon of multi-beam interference. These occur as light passes in both directions in varying degrees to create the final impression. A part of the light seems to be "imprisoned" between the layers, which improves the saturation of light (translucency).

We see all colors because the light illuminates the pigments (emission of photons). Thus, by these innumerable refractions, the multilayer glaze technique provides an incredible variation and diversity of nuances.

For example, the sky which is created with paint, based on additive mixing of several tube paints on the palette and applied in one layer more or less covering the canvas, is missing the quality of translucency and seems plain. It is possible to create the same sky with glazes in the multilayer technique with subtractive mixing directly on the canvas. Then, the final color is translucent and appears deeper; the light seems more natural and the entire presentation is more credible.

For example, the sky which is created with paint, based on additive mixing of several tube paints on the palette and applied in one layer more or less covering the canvas, is missing the quality of translucency and seems plain. It is possible to create the same sky with glazes in the multilayer technique with subtractive mixing directly on the canvas. Then, the final color is translucent and appears deeper; the light seems more natural and the entire presentation is more credible. This is for good reason. The blue color of the sky is translucent representing the atmosphere surrounding the Earth, which gives us an impression of the blue sky over the darkness of outer space. Thus, the atmosphere is similar to a glaze on a dark paint, creating a translucent blue color.

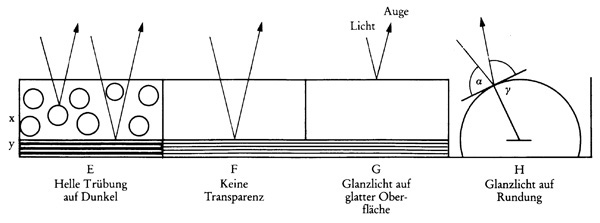

When representing natural phenomena and subjects, the multilayer painting offers clear advantages due to its close color construction of natural events and situations such as painting eyes, skin, hair, fabrics and ceramics, trees, flowers and fruits.

When representing natural phenomena and subjects, the multilayer painting offers clear advantages due to its close color construction of natural events and situations such as painting eyes, skin, hair, fabrics and ceramics, trees, flowers and fruits.In any natural object, there is something deeper, below the surface, shining through and the sum of the overlaying single colors yields a specific multidimensional impression.

The eye of the beholder inherently recognizes the natural origins of the subject without the aid of any superficial details, but by a natural effect of light saturation provided by multilayer glazes.

The eye of the beholder inherently recognizes the natural origins of the subject without the aid of any superficial details, but by a natural effect of light saturation provided by multilayer glazes.  The subtractive paint mixing follows the scientific optical rules. The following factors influence the path of the light and the translucency of the final color.

The subtractive paint mixing follows the scientific optical rules. The following factors influence the path of the light and the translucency of the final color.These examples show the lost of plasticity and natural impression of the clouds after turning away from the multi-layer technique with glazes.

A The production of the paint

A The production of the paint1. The different density of the pigments, i.e. the ratio of the "powder" to the binder.

2. Different binder formulas, such as varying quantities, different types of resin (from larch or cherry tree) or the addition of wax etc.

B The application of the painting

B The application of the painting3. The thickness of the glaze: the permeability of light decreases in relation to an increased quantity of the applied paint.

4. The sequence of the layers on the canvas. The translucent result of color is not the same when color A is shining through color B or vice versa. A + B is not equal to B + A. In mathematics the sum of 20 can be built by an addition of 1+2+4+6+7 or 4+6+7+3 or 2+9+2+4+3 etc. but in painting each variation would create a different result. Such logic does not exist in "alla prima" painting (wet-on-wet) as a premixed paint – even if sophisticated – has a unified consistency and is applied as such; any differentiation of the color can only be obtained by the quantity of the paint.

The effect of depth, warmness and luminosity is solely based on all this knowledge which is characteristic of the work of the Old Masters and of Vietinghoff's own paintings.

The effect of depth, warmness and luminosity is solely based on all this knowledge which is characteristic of the work of the Old Masters and of Vietinghoff's own paintings."A semi-transparent white paint applied on a dry and isolated black layer appears bluish, a black glaze on a white layer appear brownish. A light orange glaze on black becomes green-grayish and a glaze of Prussian blue on white turns a greenish shade etc. The Dutch and Flemish painters, namely Rubens, van Goyen and Jan Bruegel the Elder, extensively used the light and dark glazes and thus – depending on the application of the same paint on a light or on a dark glaze – achieved warm and cold grey tones of a beauty of which they could never obtain with the additive paint mixing." (Egon von Vietinghoff, Handbook of Painting Technique)

The more glazes the light hits, the more complex the interactions are. All factors contribute to vary the light's permeability.

The human eye is such a differentiated organ that it perceives almost infinite nuances depending on whether the paints are premixed and applied in one layer or applied in the multilayer technique with a translucent result. As if the eye would be able to see which figures make up the sum of 20 and in which order they were added, twenty is not simply equal to twenty; green-blue is not simply equal to green-blue.

Thereby, the multilayer technique offers to enrich the graduation in the spectrum of colors enormously. If the aim should be a bold expression or – for any other reason – no importance should be attached to translucent shades, the use of the multilayer technique may be exaggerated. A visually demanding art which advances to the core of its subjects, as Vietinghoff represents, cannot manage without it. If Vietinghoff had not used it, he would have reduced the possible spectrum dramatically, would have worked with much less plasticity and obtained only a fraction of the natural effect – similar to cooking without spices.